Cardiologist urges return to ancestral foods

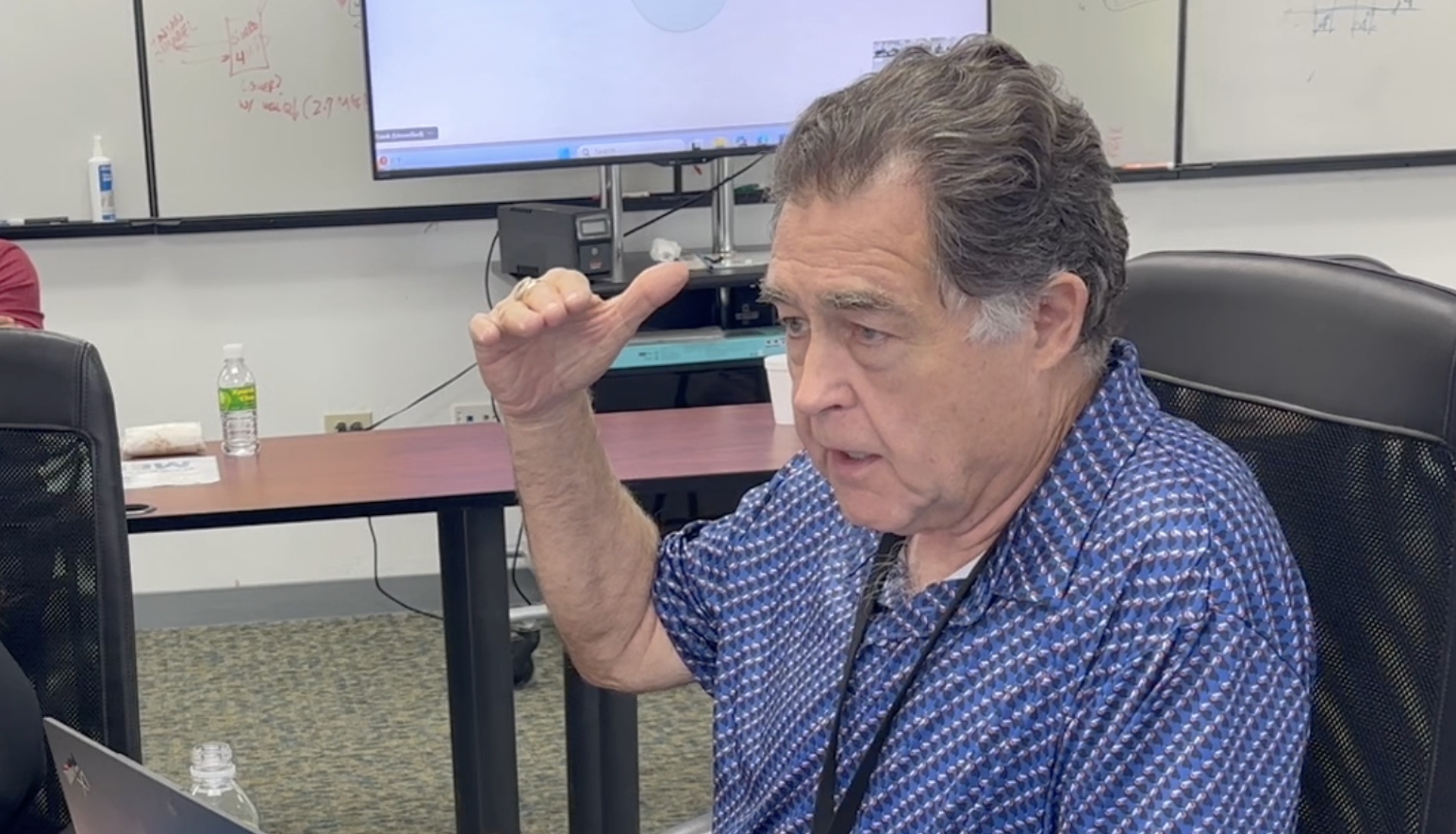

Commonwealth Health Center cardiologist Dr. Peter Gregor delivered a sweeping presentation linking the modern explosion of sugar consumption—especially fructose—to the sharp rise in obesity, diabetes, cancers, and heart disease across Micronesia and the world.

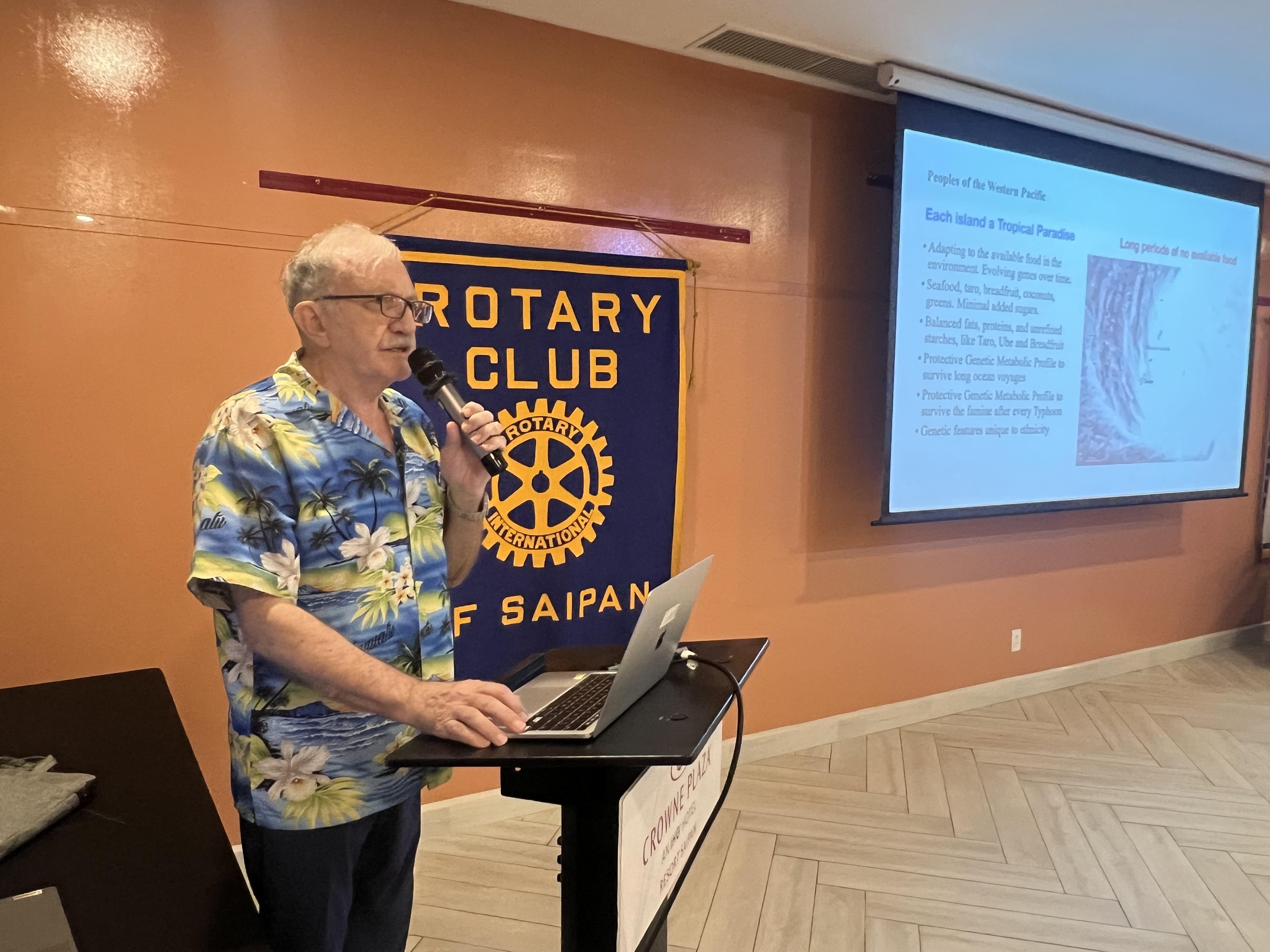

Speaking as the guest presenter at the Rotary Club of Saipan’s monthly meeting last Dec. 9 at the Crowne Plaza Resort Saipan, Gregor urged the community to return to the foods that kept human ancestors healthy for thousands of years. He encouraged a shift away from processed white breads, sugary drinks, and low-fat packaged foods that now dominate local diets.

He said Micronesians, who historically thrived on root crops such as taro and breadfruit, are genetically predisposed to suffer when exposed to high-fructose modern diets.

“In two generations, the people of Micronesia have gone from among the healthiest on the planet to the sickest—two generations! And it's rather obvious as to what's causing it. Just look at the Port of Saipan. The ships come in containers full of Western food,” Gregor said, citing genetic traits that once helped islanders survive long voyages and post-typhoon famines but now make them especially vulnerable to sugar overload.

Gregor also showed Rotarians a map produced about six months ago by the Gates Foundation and the World Health Organization, highlighting global childhood obesity and diabetes trends.

“Usually, the islands of the western Pacific don't show up on a world map because they're kind of small. But just to be sure, read that—Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Samoa are the most obese and diabetic children on the planet. And so are the under-25 adults,” he said.

The projection extended to 2050, noting that regions such as the Middle East and Mexico—areas where major beverage companies like Pepsi and Coca-Cola have concentrated significant marketing efforts—are expected to face similarly elevated levels of metabolic disease.

Gregor noted with some optimism that several Saipan bakeries are embracing his message with new products rooted in local tradition and ancestral food.

“What we've actually done is I have been telling so many of my patients to go buy taro [and] that Great Harvest is increasing the number of taro breads they're making per day. Cha Café is now making taro bread. And Herman’s [Modern Bakery] is making ube bread,” he said.

Gregor said patients who have switched to these ancestral staples—paired with eliminating what he calls the “four horsemen of the metabolic apocalypse” (white rice, white bread, sugary soda, and low-fat processed foods)—are seeing dramatic improvements. Some have lost up to 90 lbs. in six months and reversed markers such as uric acid levels and A1C.

A substantial portion of his presentation traced how traditional diets worldwide—from Inuit hunters to Aboriginal Australians to South Asians—collapsed once replaced with Western processed foods. He highlighted 1984 as a major turning point when beverage companies switched to high-fructose corn syrup and “low-fat” marketing pushed manufacturers to load foods with sugar to replace fat.

Fructose intake, he said, jumped from two pounds per person per year in 1776 to two pounds every two days today. Unlike glucose, which the body can regulate, fructose has no natural metabolic brakes and rapidly converts to fatty liver, uric acid, and toxins that fuel diabetes, obesity, gout, kidney failure, and certain cancers.

Beyond encouraging families to return to traditional foods, Gregor proposed a broader community strategy—leveling the cost of ancestral breads to compete with cheap imported white bread, integrating island-food education into school curricula, launching speech contests centered on food heritage, and fostering partnerships between local farmers and bakeries to expand production.

“What I'm suggesting here is let's try to get a little cottage industry going of local farmers and local bakeries working together to level the playing field on the cost of ancestral foods compared to Western foods. What are we doing? No, we're not attacking the food industry,” he said. “We're trying to improve the local microeconomics of these little islands.”

Gregor said he hopes Saipan can become a model for the rest of the Western Pacific and is exploring a regional medical trial to track improvements in diabetic biomarkers among those who adopt ancestral diets.

Rotary Club members applauded the presentation, noting that Gregor is a rarity among physicians for placing food at the center of disease prevention.

“We are so fortunate to have you here as a cardiologist for, in my opinion, a fantastic experience, but you're the only physician that I have ever met in my 72 years who also talks about food. You're the only one, and it's the missing link, just like you talked about today,” said Rotarian Donna Krum.

Share this article